Status

Return to homepageWatching

Animation: Existential Crisis in Class by WhatsItLike.

Song: Euthanasia Rollercoaster by KM_EXP (Everhood OST)

Playing

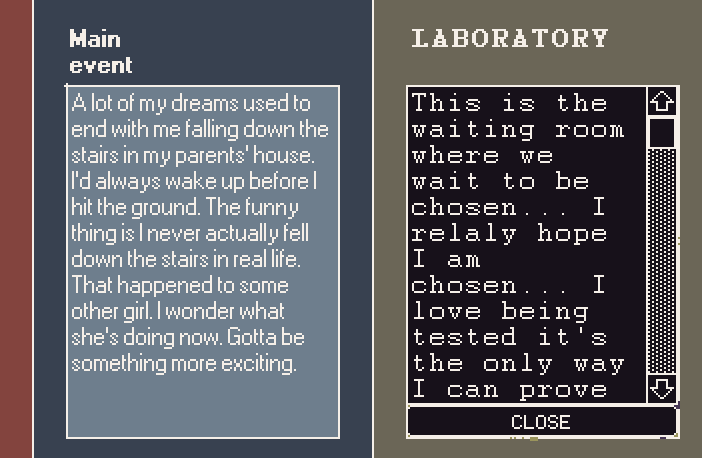

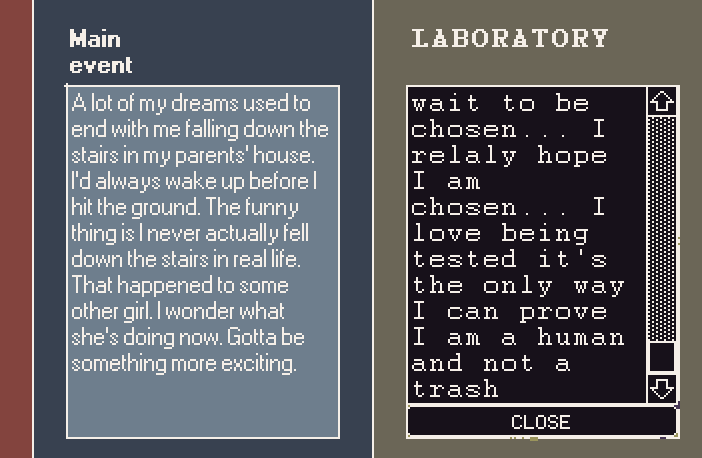

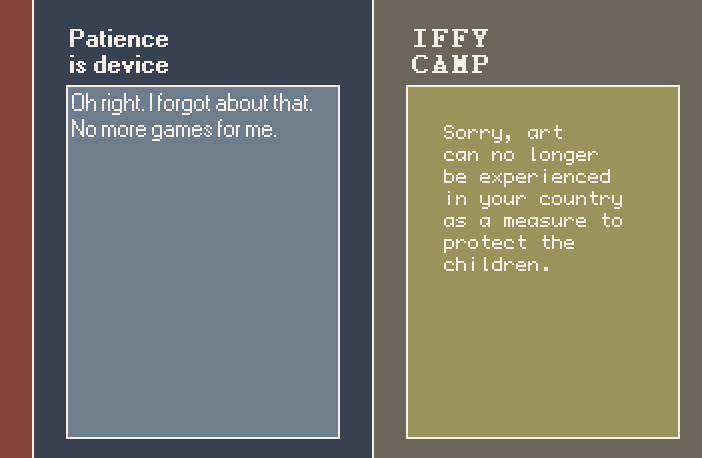

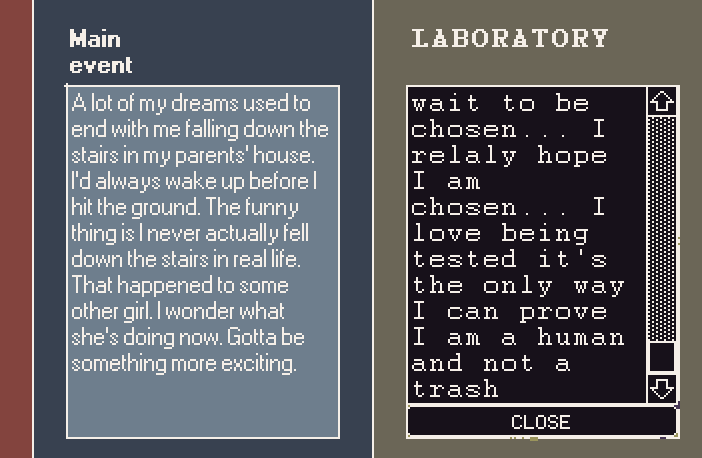

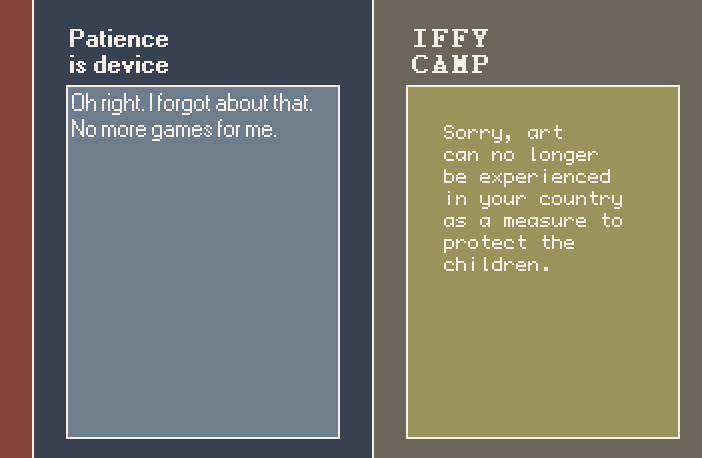

Violent Delight, by Coral Nulla

Animation: Existential Crisis in Class by WhatsItLike.

Song: Euthanasia Rollercoaster by KM_EXP (Everhood OST)

Violent Delight, by Coral Nulla